What would I be capable of if I weren’t bound by the ethics of Christian charity?

Let’s see. I might write something like this.

Earlier this week, from seemingly nowhere, I was attacked on Twitter by a complete stranger. I woke up, checked my email, and saw that some (I suppose we should call him a) person had responded to six or eight of my recent tweets in a most hostile manner.

Now let’s bear in mind the origins of these tweets of mine. Most of them were online articles I had posted links to, and the rest were little jokes forwarded from my Facebook page, ephemeral quips like:

Nothing world-shattering here, merely me obviously ready for beddy-time.

Nonetheless, our hero-from-the-Twittersphere apparently took great offense to this.

Well.

First, while we’re on the topic of mirrors, let’s just say the blurring feature I’ve used here has done the world a great favor. But to my larger concern, what could provoke such disproportionate hostility?

One might, if one were so inclined, assume that the lets-call-him-a-man who composed the response falls into the ever-useful category of “nerd.” The particular variety of geek I’m thinking of is that which so-wanted Second Life to make it big because their Actual Life was lonely and pathetic. Days spent lusting over this or that animated woman, nights occupied with online message-board arguments over authentic translations of Klingon. What have you.

The argument for this assumption is simple: the personage responsible for the Tweet seemingly has no life outside its Linux-based operating system, so it must desperately cling to the mechanisms of its tenuous relationship with what passes for social. The internet is the best option for such a …

See now here is where I get confused. I can’t quite get myself to refer to the Tweet-consciousness as a person. This is why I reject the “nerd hypothesis” I just outlined. I kind of like nerds and find them to be extremely human.

Instead, I honestly think that this… I guess for simplicity’s sake, we should call him a person… person conceives of himself as a “brand.” A product habitating a cyberspace where social awkwardness is rewarded with “followers” and body odor is irrelevant. The Onion recently captured the essence of such an individual.

I’m quite convinced of this because of the full context of our exchanges.

In addition to his defiant defense of the internet, I awoke to a barrage of insightful commentary about what he kept referring to as my “techno-phobia.” I assume from his use of this term that he thinks I’m against recognizing marriages between blenders and the iPhone 3. I’m not really sure what else it could mean.

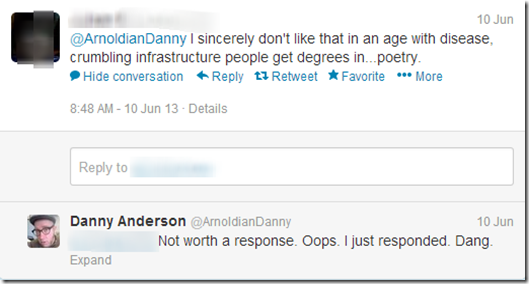

At any rate, I had, recently posted a few links to articles that were certainly critical of techno-utopianism. What’s-his-face, however, drew some starling conclusions from these posts, and his reactions were severe. For instance, I posted a link to an article that calls attention to some of the destructiveness of Silicon Valley. It’s an illuminating piece that offers a fair critique of the Sean Parker wedding. The brand responded with:

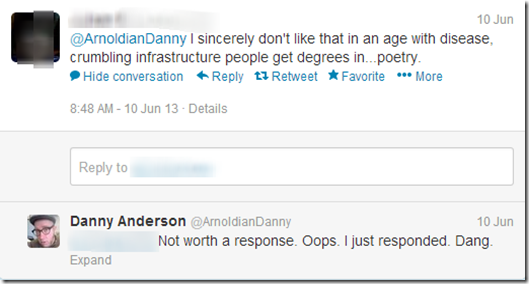

For some reason, I decided to jab back.

Alright, I’m immature. I know this already. Move on.

This wasn’t the end of his assault, either. I had also linked (at some point) to an article about attention spans and internet writing.

Here is the offending Tweet:

His response was actually a fair one, if dogmatic and defensive:

This all took place, mind you before I woke up in the morning. Without a single peep from me, our friend from the fantasy land of microchips and no girls went off:

Well, I never.

I decided to fire a shot across the bows.

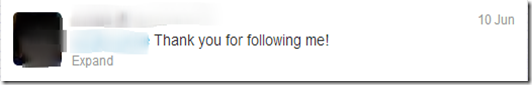

My accusation, I maintain, was spot on. I took a look at his Twitter activity and it’s pretty clear that he is driven by an attention-seeking mechanism worthy of Paris Hilton, Rasputin, and the Naked Cowboy of Times Square. A large percentage of his tweets are, like the ones he aimed at me, inflammatory, un-invited, and focused on absolute strangers. He, in fact, is a troll, looking to start fights so as to establish his “brand” as an “influencer” in the social mediasphere. When he lures someone into his acne-ridden web he responds like this:

Checkmate. A pathetic gesture that brings back memories of junior high, when the geek (usually me) guilted a moderately attractive girl to couple-skate down at the rink at 7:30 on a Friday night.

This is all on Twitter, so I can only speculate about what our friend sounds like in real life, but I imagine it’s like this:

And yes, I decided he would get nothing. And like it.

Only by nothing, I mean pushback against his egocentric techno-mania.

His witticism regarding my troll comment:

And then…

Again, I know. Immature. Youbetcha.

Then he got nasty (in the way you’d expect from someone who cuddles up to his Ewok Pillow Pet each night):

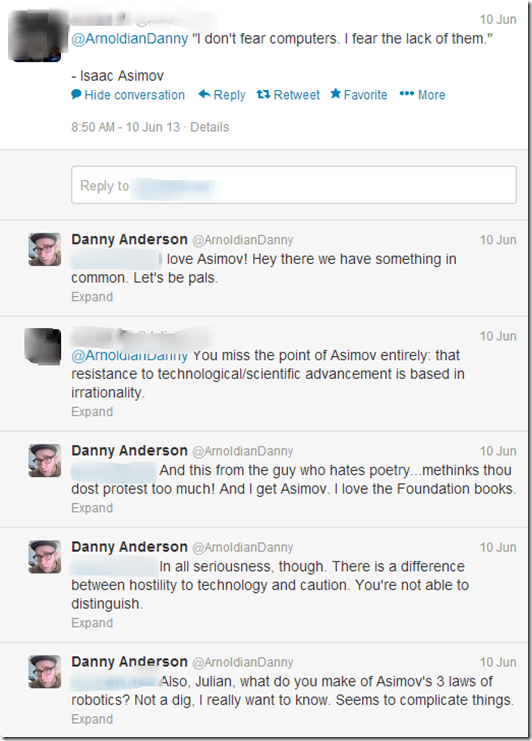

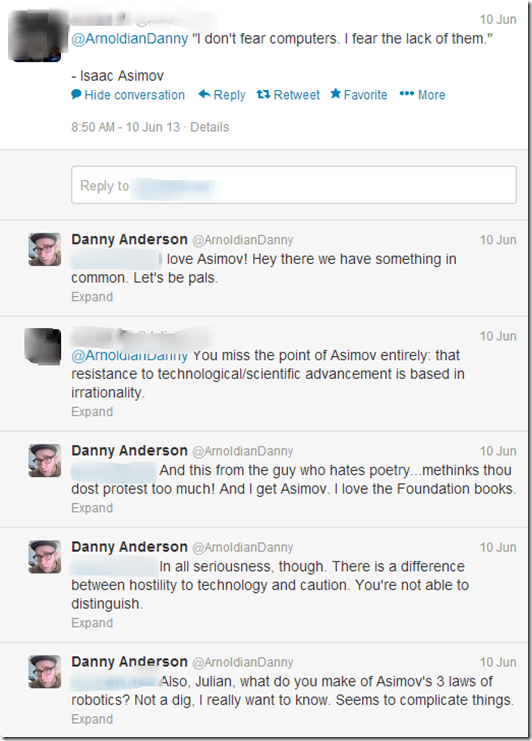

I’m having a little fun here, but I do want to make a serious point. As the conversation (if such a thing is possible on Twitter) progressed, the shallowness of his reasoning, and more importantly his worldview, revealed itself. As if he forgot his own dig at the humanities, he threw out a quote from a …gulp…novelist, Isaac Asimov. The subsequent responses are telling:

First of all, yes. His name is apparently Julian. Let it go. Focus instead on his lack of response when I brought up the specific implications of his quotation. This silence demonstrates to me that he basically found an isolated quote that, out of context, supports his narrow worldview. There is no attempt to struggle with the complications his “source” introduces in the conversation. In my freshman composition class, this merits a major point deduction.

This is the root of my caution when it comes to messianic visions of technology. The world is not written in binary code. It is impressionistic at its most clear.

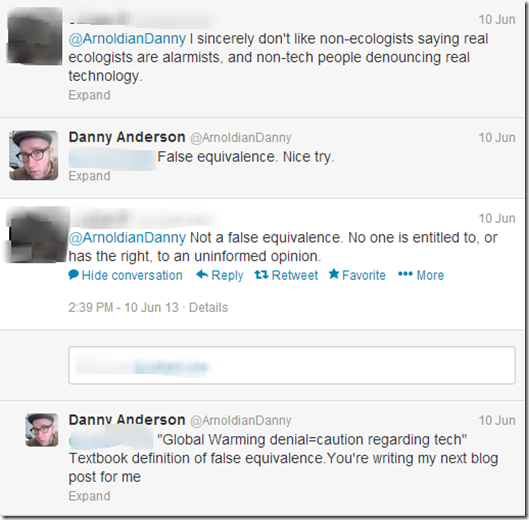

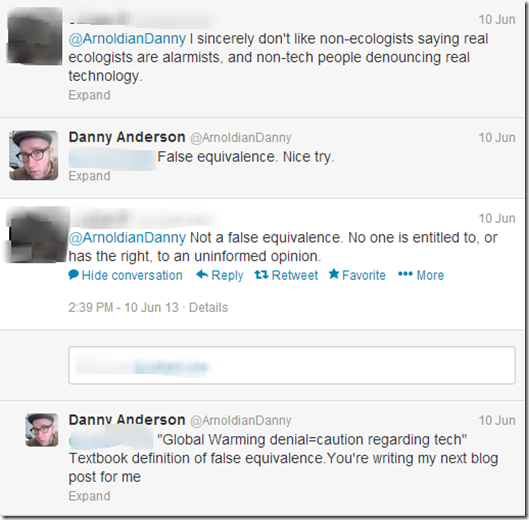

The English nerd that I am, I also scolded the logic of some of his rhetoric:

…and so here we are.

There was no immediate response, nor has there been a delayed one. The troll is never interested in depth, only the ignorant defense of ill-considered dogma — and the acquisition of “followers.” Well I will not follow a fool down a blind alley.

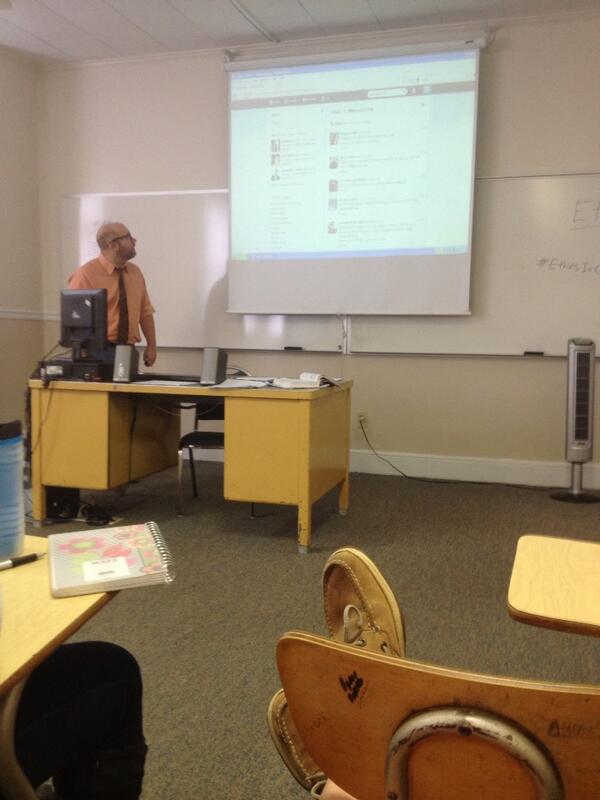

Despite this fellow’s assessment of me, I am not against technology. Case in point, I’ve employed it in the composition of this post and I use it in the classroom each day. I am, however, cautious about it. As a tool, it is wonderful. As a philosophy in and of itself? Not so fast. Just look what it has done to our poor troll’s ability to think.

Fortunately, I am bound by notions of Christian charity, so I would never write such a mean-spirited, vengeful thing as this.

Oops. Dang.

As always, I’m ever-dependent upon Grace.

Ashamed of myself,

d